Web of words, red flags

Court documents detail early warnings in alleged Ponzi scheme that ended in one of the largest bankruptcy filings born of the area's real estate collapse

By Andrew Moore

The Bulletin

February 14. 2010

Three years before Bend's Summit 1031 Exchange filed for bankruptcy, Lane Lyons, then an employee of the now defunct real estate services company, raised a red flag about the business in an e-mail to fellow employee Timothy Larkin.

Both Lyons and Larkin would become principals in the company in 2006.

The e-mail, quoted in the bankruptcy trustee's report, indicates Lyons' concern about a company called Inland Capital Corp., which the trustee's report asserts was created by Summit's two original shareholders — Mark Neuman and Brian Stevens — for the express purpose of loaning money from Summit to Inland for the personal gain of the shareholders, their families and friends, primarily through investment in Central Oregon real estate.

When Summit filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Portland in December 2008, it reported it was owed $13.7 million from Inland.

“The more I think about Inland funds, the more certain I become that without immediate liquidity in the same amount we use, if any word of it gets out we would be ruined,” Lyons wrote in 2005. “I don't necessarily mean immediate financial ruin, but more importantly, our reputations and integrity. That really bothers me.”

Lyons, Larkin, Neuman and Stevens have not been charged with any wrongdoing.

But Bankruptcy Court documents show the U.S. Department of Justice issued a grand jury subpoena for Summit's records shortly after Summit's bankruptcy filing. The trustee's report also states Summit is under investigation by the FBI and the Internal Revenue Service.

“I disagree with much of the verbiage in the report and many of the conclusions,” Lyons said in an interview Thursday. “I worked very hard to alter and stop Summit's practices then, and I've worked since then to repair and mitigate the damages caused by Summit's failures. I sincerely regret my earlier efforts weren't fully successful.”

Numerous attempts last week to seek comment from the other principals or their attorneys were unsuccessful.

In the wake of Summit's bankruptcy filing, creditors subsequently filed more than $41 million in claims against the company, making it among the largest bankruptcy filings to come out of the collapse of the housing bubble in Central Oregon.

Kevin Padrick, the court-appointed bankruptcy trustee who authored the report, also accuses Summit in the report of operating a Ponzi scheme. The sentiment was echoed by Judge Randall Dunn, the Bankruptcy Court judge overseeing Summit's case, who said the company “arguably ran a Ponzi scheme” in remarks at a hearing in Portland last May.

More than a year after Summit's bankruptcy filing, the case continues to wind its way through Bankruptcy Court. It's also spawned a number of lawsuits, including a $30 million suit against Umpqua Bank brought by Padrick in which he accuses the bank of aiding and abetting Summit in the scheme.

Umpqua was Summit's primary bank, and Padrick alleges in the suit that Umpqua learned of Summit's activities in 2007 when Summit and the bank discussed a strategic partnership.

Steven Philpott, general counsel for Umpqua Holdings Corp., the bank's parent company, wrote in a statement e-mailed to The Bulletin that “Umpqua chose not to pursue Summit's proposal. When Summit presented its proposal, its principals never revealed to the bank, nor was the bank ever aware of, any illegal activity on the part of Summit.”

Padrick is now working to liquidate Summit's assets for the benefit of roughly 150 creditors, mainly Summit's exchange clients.

Summit's bankruptcy was converted from a Chapter 11 reorganization to a Chapter 11 liquidation last year after Padrick and the creditors decided liquidation would be in the creditors' best interest, according to Bankruptcy Court documents.

Padrick's 78-page trustee's report explains in detail the results of his “forensic accounting investigation” into the company, which he describes in the report as “extensive and complex.”

He writes of combing through 600 boxes of Summit documents, 100,000 e-mails spread between seven computer servers and more than 500,000 entries in Summit's accounting database in an attempt to make sense of the company's business dealings.

Those dealings also include roughly 240 property investments spread between more than 100 separate entities, including many limited liability companies controlled by the shareholders that received loans from Inland.

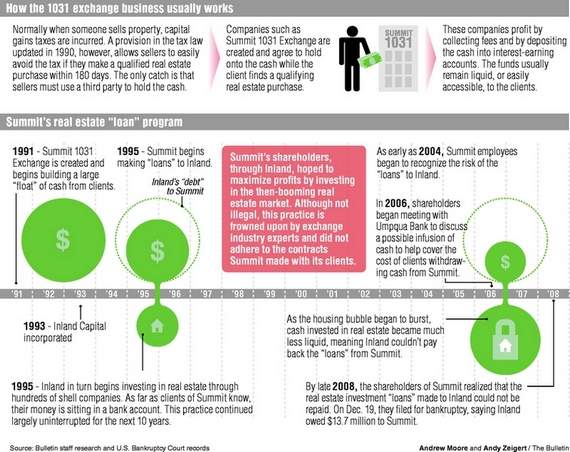

Summit's primary business was facilitating 1031 exchanges, complex real estate transactions that help real estate investors defer capital gains taxes.

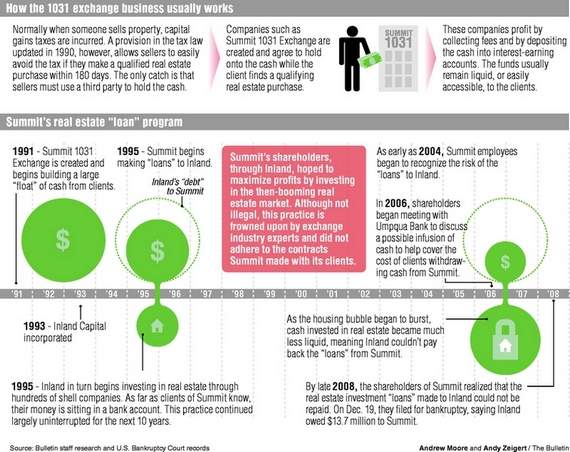

But as early as 1995, and certainly by 1997, according to the report, Neuman and Stevens started transferring money from Summit to Inland and began weaving the tangled web that Padrick is working to unravel today.

Beginnings

Summit was incorporated in May 1991 as Summit Accommodators Inc. by Neuman, Stevens and a third individual the report doesn't name. The company established the business name Summit 1031 Exchange in 2006.

According to the report, Neuman and Stevens were certified public accountants who had practiced together since the early 1980s who formed their own practice — Stevens & Neuman LLP — in 1989.

Padrick asserts that the formation of Summit was likely an outgrowth of their accounting practice, as accountants frequently refer clients to qualified intermediaries.

In the 1031 exchange industry, companies such as Summit typically earn income by charging their clients fees, as well as taking a portion of the interest income their clients' money earns while it is parked in a bank.

At times, Summit held more than $100 million in client money, according to the report.

But in the lightly regulated 1031 exchange industry, no laws specify where a client's money can be placed.

Industry standards, published by the Federation of Exchange Accommodators, a prominent trade association, say that 1031 exchange companies should keep their clients' money liquid, should preserve principal and should not commingle clients' money with other funds.

Those standards were put forth many years after Summit went into business.

However, Summit, in its contracts with exchange clients, stated it would place its clients' money into “deposit accounts” at “financial institutions” and use those funds only to accomplish the contracted exchange, according to the report.

But, according to the report, Summit's shareholders began loaning funds from exchange clients to themselves, to entities they controlled or to other third parties through Inland.

“It is the Trustee's conclusion,” Padrick writes in his report, “that this conduct was fraudulent because at the time the Exchange Agreements were being executed between the new clients and Summit, the shareholders knew that they were using new exchange clients' funds to fund existing clients' purchase of replacement property, make refunds or make ‘loans' to Inland, and those funds were not being held in a financial institution for the purpose of completing the new client's purchase of replacement property.

“It is the Trustee's conclusion,” Padrick continued, “that such conduct constituted theft by deception.”

Inland Capital

Inland was incorporated in December 1993 by Neuman, Stevens and the third shareholder, who was bought out in May 1998 according to a pre-existing buyout agreement.

By 1997, the earliest Padrick can find accounting records, Summit began transferring client funds to Inland. A “note receivable” was recorded on Summit's books to account for the transfer.

According to Padrick's report, Inland's sole activity was to receive client funds from Summit and then “loan” the money predominantly to the shareholders, their friends and family, and entities owned by them, for their use. Inland loaned money to more than 100 entities and individuals, the report says.

“Summit did not own any part of Inland and was not entitled to any value generated by Inland,” Padrick writes in the report. “From a risk-benefit perspective, the risk of loss of exchange clients' funds was borne by the exchange clients and the benefits inured to the shareholders.”

In the report, Padrick argues that the transfers between Summit and Inland and then from Inland to the other entities were characterized as loans but lacked any typical loan characteristics.

Padrick writes that he was unable to find loan agreements or promissory notes between Inland, Summit or the entities, nor documents detailing underwriting decisions.

Padrick also writes that he can find no evidence Inland was ever capitalized with any funds other than transfers from Summit, and that accounting records show Inland had only one employee, and only for six months in 2005.

“The Trustee has concluded the Summit-Inland relationship was not legitimate,” Padrick concludes in the report. “When the (Summit) shareholders wanted money at Inland they simply caused the transfer of (funds) from the unknowing exchange clients to occur. The ‘formality' of creating a ‘note receivable' account was to make sure the books balanced.”

Padrick estimates that from 1997 to 2008, through the use of Inland, Summit's shareholders directly or indirectly diverted to themselves more than $66.5 million in exchange clients' funds.

Additional Bankruptcy Court documents show that between 1997 and 2008, roughly 28 percent of the total funds brought to Summit by exchange clients were loaned to Inland.

Where did the money go?

After Summit's shareholders agreed to turn over control of most of their assets as part of the bankruptcy proceeding, Padrick assumed control of roughly 140 properties to be liquidated for creditors.

The properties, mostly in Central Oregon, included 19 residential or commercial development projects, 11 income-producing properties, such as apartment complexes, two mobile-home parks, 80 finished lots and 29 single-family residences.

Money also went for the shareholders' personal use, Padrick wrote.

According to the report, Neuman used at least $618,000 of exchange client funds to obtain a $2 million loan from a third-party mortgage company to build an 8,070-square-foot home — complete with a swimming pool and tennis court — in Bend's Cascade Highlands subdivision.

Padrick also asserts that Neuman used exchange client funds routed through Inland to make a down payment on a home for his daughter, and that Neuman and Stevens made direct loans to various other people and entities.

Ultimately, the money transferred from Summit to Inland created a hole in Summit's books that could not be quickly filled once the real estate market began to collapse and it became harder to sell Inland property to repay Summit. There were not enough funds on hand at Summit to satisfy the demands of its clients, according to the report.

Summit had a “liquidity crisis,” said Padrick.

Lyons and Larkin

Larkin joined Summit in 2002 and was its director of operations. Lyons, a tax attorney, joined Summit in June 2005 and was the director of legal and tax policy.

In January 2006, Lyons and Larkin became equal shareholders with Neuman and Stevens in Summit and Inland, according to Padrick's report. Each owned an equal 25 percent stake in the corporations and various other entities affiliated with Neuman and Stevens.

According to the report, Lyons and Larkin purchased their shares for $500,000 each.

However, it was Lyons and Larkin, according to the report, who first began raising red flags about Summit's lack of funds due to its “loans” to Inland, and who would ultimately come to rue their involvement with Summit.

In 2006, new loans from Summit to Inland began to decrease significantly, though they didn't stop completely until January 2008, according to Bankruptcy Court documents.

In 2007, Larkin wrote an e-mail to Neuman, Stevens and Lyons saying action was needed to resolve the “Inland problem.” The e-mail, included in the report, also suggests Larkin was aware of Summit's liquidity problems as early as 2004 based on a memo he sent then.

Wrote Larkin: “This Inland problem did not start yesterday (my first memo went out in 2004) and many times over the last couple years, you have come to the conclusion that we will have to suck it up and pay tax in order to pay down Inland only to have you kill a strategy because of the tax ramifications.”

It's not clear from the e-mail or trustee's report if Larkin is addressing one or all of the partners, but he discusses a plan to make Summit whole by selling Inland assets, even though it would mean a substantial capital gains tax bill.

“I don't want to re-hash old stuff continually,” Larkin continued in the e-mail. “But the brutal fact is that our current model is a recipe for failure.”

Umpqua Bank

Part of the principals' efforts to resolve Summit's liquidity problem included exploring some sort of strategic relationship with Umpqua, Padrick writes in the report, including a roughly $15 million line of credit from Umpqua to Summit secured by Inland's assets.

On March 1, 2007, Umpqua executed a nondisclosure agreement with Summit, according to Padrick's report. The same day, Lyons sent a memo to Umpqua officials, including CEO Ray Davis, that “comprehensively described Summit, and more importantly, Inland,” according to Padrick.

As quoted in the report, Lyons' memo said, “Inland has served as a conduit whereby Summit loaned Inland the funds at a premium over Summit's bank rate of earnings, and Inland would either loan the funds to local businesses and/or investors for business or real estate projects, or would invest the funds directly in real estate selected by Summit's principals.”

Umpqua ultimately decided against making a loan to Summit.

But Padrick argues in the report that because Umpqua learned Summit was diverting money to Inland despite Summit's contracts with its clients but did nothing about it, and continued its business relationship with Summit, the bank aided and abetted Summit's practices.

Further proof Umpqua knew Summit was acting fraudulently is an e-mail Umpqua's chief credit officer, Brad Copeland, wrote to Davis in December 2008, after Summit's bankruptcy, Padrick argues in the report.

“I'm sure glad we didn't get in bed with these guys,” Copeland wrote. “I suspect there are some significant fraud issues involved and our records will all be subpoenaed. This will probably get very ugly.”

Philpott, the bank's general counsel, said in his statement e-mailed to The Bulletin that “Summit had multiple banking relationships. During Umpqua's business relationship with Summit, we, along with other banks, continued to provide depository services. There was no reason for us, or any bank, not to accept their deposits.”

As the bankruptcy trustee, Padrick is legally obligated to take whatever steps he can to collect money for the creditors, which allows him to sue third parties, such as Umpqua.

Philpott argues that power gives Padrick an additional motive, since Padrick keeps a portion of the money he earns for creditors.

“Keep in mind that Padrick, as a bankruptcy trustee, tries to collect as much as possible for the benefit of the bankruptcy estate,” Philpott wrote in his statement. “The trustee is not a neutral participant or fact-finder. In his case against Umpqua, he is the plaintiff asserting a claim and the more he collects, the more he is paid and the more the estate's creditors are awarded.”

In response, Padrick said in an statement e-mailed to The Bulletin that his role as trustee “is that of a factual investigator and upon finding wrongful conduct that caused damage, the trustee's role and obligation are to pursue Umpqua Bank, the shareholders, and anyone else who wrongfully caused damage to Summit's clients.”

Philpott also argues that Umpqua did not commit any wrongdoing due to a pending settlement in an additional suit Padrick filed against Summit's four principals. Padrick's allegations in the suit include breach of fiduciary duties to their exchange clients, professional negligence and civil conspiracy, among others.

The suit is an adversary proceeding included in the bankruptcy.

Philpott, who has not seen the pending settlement but is aware of its basic terms as relayed to him by lawyers involved in the matter, said it works in Umpqua's favor.

“Recently, Padrick agreed to settle the claims he asserted against the shareholders of bankrupt Summit,” Philpott wrote in his statement. “In the settlement, the trustee dismissed accusations that these principals breached their ‘fiduciary duty' to their company and its clients. So, the trustee has dropped the heart of his case against Summit's shareholders while continuing to pursue Umpqua Bank for ‘aiding and abetting' these very same shareholders.”

In response, Padrick said Philpott's statement “is inaccurate and misleading. The settlement agreement will speak for itself.”

Padrick's suit against Umpqua was filed in Multnomah County Circuit Court, but attorneys for Umpqua argued it should be included in Summit's bankruptcy proceeding. However, Padrick and his attorney successfully asked Judge Dunn, of the Bankruptcy Court, to remand the suit back to state court.

A trial date in Multnomah County Circuit Court has not been scheduled, but a hearing to assign a judge to the case is scheduled for Tuesday.

Endgame

In 2007, as the real estate market began to soften, fewer exchange clients came to Summit, which now included affiliate offices 50 percent owned by the company in eight Western locations.

As Padrick asserts in the report, because Summit loaned Inland money, which was often tied up in the shareholders' various real estate investments, the only way Summit could fulfill its obligations to existing exchange clients was with money from new clients.

“This fact pattern,” Padrick says in the report, “of new clients' funds being used to purchase replacement property for existing clients has consistently been found by courts to constitute a ‘Ponzi scheme.'”

Philpott argues Summit did not operate a Ponzi scheme, and had the money to fund its client obligations based on the sale of and revenue generated from assets purchased through Inland. Philpott said Neuman and Stevens were reluctant to sell assets because of the capital gains taxes they would incur.

“Clearly, the Bend real estate market saw some very strong activity during the period between 1997 and 2008 and sales and loans were possible,” Philpott wrote in his statement to The Bulletin.

With fewer clients, Summit's “liquidity crisis” grew, Padrick writes in the report, and the declining real estate market made it difficult for the shareholders to recoup the exchange client funds from Inland that were invested in real estate.

“While it is possible to make significant profits from the unlimited use of other people's money, it is equally possible to generate significant losses,” Padrick writes in the report. “As soon as the real estate cycle in Central Oregon was on its way down, the result to Summit was inevitable.”

In November 2008, Padrick states Neuman sent an e-mail to the shareholders proposing Summit purchase another 1031 exchange company to resolve its liquidity crisis. The proposal was never acted upon.

By December 2008, the handwriting was on the wall.

According to the report, on Dec. 9, 2008, 10 days before Summit's bankruptcy filing, Lyons wrote an e-mail to a Summit employee asking if he had removed “the language re security of funds from the website?”

The same day, Larkin wrote an e-mail to the shareholders:

“I find it particularly frustrating that I had to fight for so long to try to bring sense to the whole Inland problem only to find myself in having to take the lead in solving a problem I had warned against all along,” wrote Larkin, according to the report. “I want you to work with all you have financially and legally to shelter your partners from the fall out of your decisions.”

Lyons responded to Larkin's e-mail: “From the day I got here, I howled about the Inland situation and got the same responses Tim (Larkin) cites. I know your intention was to try and help Tim and I build some net worth, but it didn't work out that way.

“I'd be lying,” Lyons continued, “if I didn't say that I'm deeply saddened that I brought an impeccable reputation into this and inherited a problem in the process that wasn't of my creation which now will likely result in me leaving here with less professional integrity than I once had and based on advice from counsel last week, a good chance at losing my license and livelihood for some period of time.”

Aftermath

Lyons now works as a sole practitioner in Bend. He is an active member of the Oregon State Bar.

Since the bankruptcy filing, Padrick reports that Lyons, Larkin and Stevens have cooperated with his efforts to unwind Summit's and Inland's business dealings. Padrick alternatively states that Neuman “has not only been uncooperative, but he has attempted to actively thwart the Trustee's efforts.”

In the report, Padrick notes that Lyons and Larkin had for years tried to get Neuman and Stevens to liquidate the speculative real estate investments funded through Inland. He also notes that Lyons' and Larkin's use of Inland funds was a small fraction of that of Neuman and Stevens.

“The Trustee does not know what influenced Larkin and Lyons to stay,” Padrick writes in the report. “The Trustee does not know why Larkin and Lyons did not report the conduct, about which they complained so vociferously, to the authorities.”

But Padrick notes that Lyons and Larkin had been assured by Neuman in an e-mail when they were “buying” into Summit and Inland that in five years the two of them “would have built enough real estate equity through Inland to ‘pull out of Summit operations.'”

In a letter by Neuman written either late August or early September 2009 posted at www.summit 1031bkjustice.com — a Web site operated by Neuman's daughter, Stephanie Studebaker-DeYoung — Neuman wrote that “I'm truly sorry for the pain it has caused all of the exchangers. I can only sincerely hope and pray that the assets we provided and any other monies available will result in the exchangers being made whole.”

Neuman added that neither Lyons nor Larkin “benefited personally from company loans in a significant way” and that “these men are not responsible for the Summit debacle.”

While the legal wrangling continues, the creditors have received at least 40 percent of their money lost to Summit, according to creditors and previous interviews with the attorney for the creditors' committee.

Bend resident Jack Robson, a creditor who initially lost roughly $50,000, says he thinks the return would be greater if there weren't so many attorneys involved. But he's not upset with Summit, he said.

“At the end of day, some people have lost a good portion of their retirement, and that sucks, but there is no malice involved in my experience,” Robson said. “They made poor decisions, and certainly who would have thought this would have been a possible outcome?”

Andrew Moore can be reached at 541-617-7820 or at amoore@bendbulletin.com.

What is a 1031 exchange?

Summit facilitated 1031 exchanges, federally sanctioned real estate transactions that allow property owners to defer the capital gains tax from the sale of a business or investment property if they purchase a similar property with equal or greater value within 180 days.

The reasoning for the provision — as stated by the Federation of Exchange Accommodators, a prominent 1031 exchange trade association — is that when an investor sells property and purchases a similar property of equal or greater value, the investor does not have the funds to pay capital gains taxes because the money from the sale has been reinvested in the new property.

In other words, the capital gain is a “paper gain” only.

According to the FEA, a form of 1031 exchanges has existed in U.S. tax code since 1923, but the process was clarified by Congress in 1990.

A caveat of a 1031 exchange, which is named after Section 1031 of the U.S. tax code, is that money from the sale of the property cannot be handled by the property owner; it must be processed through a third party. In the 1031 exchange industry, the third party is referred to as a “qualified intermediary.” Summit acted as a qualified intermediary in such transactions.

According to industry standards, during the 180 days after a client sells a property and before he or she buys a new one, the qualified intermediary typically keeps the client's money in a bank account or some other liquid investment that can be easily converted to cash to purchase the client's new property.

The 1031 provision is different from the $250,000 capital gains tax exclusion that individuals ($500,000 for married couples filing jointly) can claim from the sale of a primary residence.

Key players in the Summit case

Mark Neuman co-founded what became Summit 1031 Exchange in 1991. He earned a bachelor's

degree in radio and television news from Eastern Washington University and a second

degree in accounting from Central Washington University. He is a certified public

accountant and received the certified exchange specialist designation in 2003.

Brian Stevens co-founded Summit with Neuman. Stevens earned a chemistry degree from Occidental College and a master's of business administration from the University of Washington. He is also a certified public accountant.

Timothy Larkin joined Summit in 2002 and served as director of operations for the company.

Lane Lyons joined Summit in 2005 and served as director of legal and tax policy. He obtained his law degree from Willamette University College of Law, holds a master's of law in taxation from the University of Washington and is a member of the Oregon State Bar.

Source: Bankruptcy trustee's report, citing biography data from Summit 1031 Exchange's Web site (now defunct)

Correction

February 17 2010

In a story headlined “Web of words, red flags,” which appeared Sunday, Feb. 14, on Page A1, the amount of money creditor Jack Robson initially lost to Summit 1031 was reported incorrectly. Robson initially lost $1,034.

The Bulletin regrets the error.

Copyright 2010