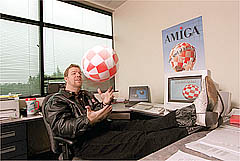

Dan Lamont/ Corbis Sygma, for The New York Times

Bill McEwen, president of Amiga, hopes to revive what has become a quaint but well-loved relic of the PC past. A half-million old Amiga computers are believed to be still in use.

The Return of a Desktop Cult Classic (No, Not the Mac)

Long Revered for Its Powerful Graphics and Lean Operating System, the Amiga Is Re-emerging From the Margins

By Katie Hafner

The New York Times

June 22, 2000

It is the little computer that won't. Die, that is.

For years, the little Amiga, a machine regarded highly but not widely, has been considered all but extinct.

But in a new chapter in the life of the Amiga's parent company, Amiga Inc., which spent years being shunted from foster home to foster home, the Amiga has finally found an owner who is determined not only to keep it alive but also to make it thrive.

Last December, Bill McEwen, a 38-year-old former truck driver, bought Amiga's remaining assets, and earlier this month his freshly minted Amiga Inc. released a software developers' kit for programmers writing applications for a new version of the Amiga operating system. Those applications will run on a new Amiga that is expected to be on the market by the end of the year. Like the old Amigas, the new one promises a lean operating system (that boots up quickly) and good graphics.

Dan Lamont/ Corbis Sygma, for The New York Times

Bill McEwen, president of Amiga, hopes to revive what has become a quaint but well-loved

relic of the PC past. A half-million old Amiga computers are believed to be still

in use.

As Amiga loyalists go -- and they are a fanatical bunch who make Apple partisans look apathetic -- Mr. McEwen came late to the fold. But he is determined to see the Amiga operating system make its way onto computers, personal digital assistants and cell phones everywhere.

"We refer to it as the VW bug," Mr. McEwen said. "It was so popular because it was functional, it did what it was supposed to do, and ahead of its time in so many ways, and then they brought it back."

Since the first Amiga was introduced in 1985, when a memorable demonstration of "Boing," a red and white bouncing ball, showed off the machine's ability to handle color, animation and sound, it has been cherished by its owners. Andy Warhol was among its early fans. Lemmings, Sensible Soccer and Sim City games all started out on the Amiga.

But the computer failed to attract a critical mass, and for years it has been considered a quaint relic of the personal computing past.

Some 7 million Amigas have been sold worldwide (compared with the 475 million machines running Microsoft's Windows, and 31 million Macintoshes, according to Dataquest, a market research company). And of those, some 500,000 are still used, with varying degrees of ardency, said Andrew Korn, editor of Amiga Active, a British magazine that is one of dozens of publications dedicated to the topic of the Amiga.

The computer has a small but fiercely loyal following, especially in Europe. Amigans, as they call themselves, hold up the computer, with its streamlined operating system, as the antithesis of today's PC's, which they consider to be bloated with code. While the Windows operating system takes more than 600 megabytes of disk space, the new Amiga's operating system takes only 5 megabytes.

Mr. Korn said that at Amiga trade shows around the world -- attended by anywhere from 500 to 2,000 Amigans -- he had seen people with their heads shaved and dyed in the red-and-white checkered pattern of the original Boing ball, which has become the computer's de facto logo. He has seen people with Boing tattoos and people in double-breasted, custom-tailored red-and-white checkered suits.

When it comes to raw computing power, the Amiga is an anemic little machine.

Still, it continues to show up in surprising places. The actor Dick Van Dyke owns three. NASA uses them, and so does a small cadre of Disney animators.

Mr. Van Dyke said he bought his first Amiga in 1991 and quickly became hooked. "I just plugged it in and turned it on and started doing animations," said Mr. Van Dyke, who uses his Amiga for 3-D animation and special effects.

Mr. Van Dyke said he had Amiga bumper stickers on his car and regularly drove to Los Angeles from his home in Malibu to attend meetings of the small but active local users group. "We're rabid," he said.

Mr. Korn said, "Like with car owners, there are a lot of people who love the machine, but the reason is because of what they can do with it rather than what it is."

After Commodore, Amiga's parent company, folded in 1994, it sold its Amiga computer line to a German computer retailer, Escom A.G. But there, too, the computer languished and production stopped altogether when Escom went bankrupt in 1996.

In 1997, prospects brightened when the PC manufacturer Gateway bought Amiga and promised to bring out a new, more powerful computer. Mr. McEwen said Gateway had mostly been interested in Amiga's 40 or so valuable patents, for video and sound card technologies.

Gateway hired Mr. McEwen, a large, lumbering man who went into computer sales after leaving his family's trucking business in the mid-1980's, as its chief evangelist for the Amiga. Mr. McEwen had not owned an Amiga before but was immediately smitten and soon came to consider himself one of the clan.

But after two years and a series of false starts, a new Amiga failed to materialize.

Last August, it looked as though the end had finally come. That's when Mr. McEwen and most members of Gateway's small Amiga team lost their jobs and plans for resurrecting the computer were scrapped yet again.

The Amiga did not fit with the company's "evolution and strategic direction," said John Spelich, a spokesman for Gateway.

Mr. McEwen put a finer point on it. "Amiga was baggage to Gateway's main business," he said. "It wasn't an asset in their minds."

So passionate had Mr. McEwen become about the computer that he quickly proposed to Gateway that he buy what remained of Amiga's assets. It took him a month to raise the money to buy the rights to the Amiga name; the remaining Amiga inventory, which consisted of some 17,000 machines in Germany; and a worldwide distribution channel already in place. Gateway kept the patents and licensed them to Mr. McEwen. The price for everything, Mr. McEwen said, was "in the millions."

Mr. McEwen now has a staff of 20 in an office in Snoqualmie, Wash., east of Seattle. All but two employees got their start in computers with Amigas, he said proudly.

Mr. McEwen recruited his director of technical support, Gary Peake, from the ranks of the most serious users. Mr. Peake, 48, who moved from Houston to work for Mr. McEwen, presides over Team Amiga, a vocal group of stalwart fans who provide technical support for other Amiga users and developers.

Mr. Peake also owns one of the three Amiga computers that can be found at the Snoqualmie headquarters. The rest of the office has PC's, which can run with the new Amiga operating system.

The spacious quarters leave plenty of room for expansion, and Mr. McEwen plans to fill every square inch. He is currently seeking second-round financing for his new venture.

Mr. McEwen keeps a copy of the Bible on his desk.

"Every so often a little inspiration helps," he said.

He travels to Amiga trade shows around the world. At a recent show in Düsseldorf, where he went to show off the new software developers' kit, some 1,800 people attended his presentations.

Mr. McEwen said he had no plans for Amiga itself to build a new machine. He is negotiating with a third-party hardware manufacturer that will build a new desktop computer by using readily available graphics chips, network cards and other components. The new machine, which Mr. McEwen said would be priced at around $700, will be called the Amiga One. "I'm starting over," he said.

In the meantime, if you're in the United States looking for an Amiga to buy, you won't have an easy time of it. That is because most of the existing inventory conforms to European, not American, video formats.

But Mr. McEwen said he was far more interested in promoting the Amiga operating system than any piece of hardware.

To that end, he has teamed up with a software company in Reading, England, to overhaul the original operating system.

Mr. McEwen said the new system was so versatile that it could be adapted to operate not only on desktop computers but also on Web appliances and cell phones. Mr. McEwen said a number of consumer electronics companies were interested in the new Amiga operating system.

"It will run on a lot of different hardware," Mr. Korn said. "Software written for it will run on whatever the underlying hardware is."

Amiga's new operating system also runs existing Amiga applications through emulation software.

Wayne Hunt, a 34-year-old software engineer in Huntsville, Ala., who runs a Web site devoted to Amiga support, said the latest developments had inspired optimism but also caution among his fellow Amigans. "It's hard when you've been sitting here for 15 years, waiting for the thing to take off like you knew it could," he said.

This time around, Mr. McEwen said, he is determined not to disappoint the likes of Mr. Hunt. "When the Amiga came out the first time, it was revolutionary and that's what we're setting out to do again," he said. "It will work. There's no doubt in my mind that it will work."

Copyright 2000 The New York Times Company